The Story behind the Eagle’s Nest

Read on to understand to understand why Berchtesgaden and the Obersalzberg were chosen by the National Socialists as their second seat of power, and why all that remains intact today is the Eagle’s Nest.

- 1. The early Obersalzberg: Pioneers of alpine tourism in the late 19th century

- 2. Hitler becomes a frequent visitor to the Obersalzberg

- 3. The transformation begins: The old Obersalzberg gives way to the new chancellor

- 4. Takeover of Obersalzberg: A second seat of power for the Nazi party emerges

- 5. Transformation of the Obersalzberg

- 6. Construction of the Eagle’s Nest and Eagle’s Nest Road

- 7. Use of the Eagle’s Nest from 1938 to 1945

- 8. The allied air raid of April 1945 and survival of the Eagle’s nest

- 9. Use of the Eagle’s Nest after 1945

- 10. A new millennium: The Documentation Centre and a five star hotel

1. The early Obersalzberg: Pioneers of alpine tourism in the late 19th century

The community of guesthouses, family farms and businesses that once called the Obersalzberg home are the main reason this area became a key location in modern history and home to what we today call the Eagle’s Nest, a compact structure perched atop the Kehlstein mountain some 1834m (6017ft) above sea level.

Our story begins in 1877 with the opening of guesthouse Pension Mortiz on the Obersalzberg by Mauritia Mayer. This conversion of a neglected alpine farm was the spark that started the transformation of the quiet mountainside village of Obersalzberg into a well-heeled tourist destination just a stone’s throw from the town of Berchtesgaden, where at the time, the Bavarian Royal Family had recently taken up summer residence.

Once Mayer had pioneered the concept of guesthouses on the Obersalzberg, further villas and farms were converted into guesthouses and inns to take advantage of the growing popularity of the area as an exclusive alpine wellness resort. Educated and aristocratic visitors flocked to the area, the focus of which remained guesthouse Pension Moritz, where contemporary personalities from the arts such as Richard Voss and pianist Clara Schumann could often be found.

Some of these well-heeled tourists went a step further and purchased homes on the Obersalzberg, amongst them the family Bechstein of piano-manufacturing fame and Carl von Linde, renowned pioneer of refrigeration.

Between 1890 and 1921 it is estimated that tourist numbers on the Obersalzberg increased six-fold, from around 6,000 to 36,000 per year.

Amongst the visitors to Pension Moritz in 1923 was a man named Dietrich Eckart. Eckart had his roots in the Munich-based right-wing press of the day and was closely aligned with the newly formed National Socialist German Workers’ Party – the Nazi party. He was mentor to the party’s young star speaker, Adolf Hitler.

In 1923 state prosecutors had issued a warrant for Eckart’s arrest as a consequence of his vicious anti-Semitic attacks on the president of Germany. Having dismissed his court summons, Eckart was now on the run from the law. To evade arrest, the National Socialists arranged for him to be secretly moved from Munich to Pension Moritz on the Obersalzberg, where he could lie low thanks to the guesthouse being under the management of a party loyalist.

In this remote corner of Germany under the alias of “Dr Hoffman”, Eckart could avoid recognition and was just few kilometres away from the Austrian border in case a fast getaway was called for. Once successfully installed at Pension Moritz, Eckart was visited by his young understudy who was also travelling in disguise. It would be the very first visit of “Herr Wolf” – aka Adolf Hitler – to the Obersalzberg.

2. Hitler becomes a frequent visitor to the Obersalzberg

When Hitler arrived at the Obersalzberg in 1923 to meet with Dietrich Eckart, it was his first ever visit. He arrived after nightfall and, having briefly called in on his mentor-in-hiding, he took a room of his own at Pension Moritz. It was only when he rose the morning after that the magnificent scenery would finally reveal itself. At that moment, the Obersalzberg cast a spell that would last until Hitler’s death in April 1945

Hitler was particularly taken by the mighty Untersberg mountain range since it had significant geographical and mythological meaning to him.

Legend had it that Emperor Charlemagne (Charles the Great), leader of the Holy Roman Empire, slept within the Untersberg range with an army, ready to rise again and save the German people when called upon – this is precisely the story that Hitler wanted to become part of himself.

This mythology coupled with the beauty of the mountains no doubt influenced Hitler, as he made many subsequent trips to Obersalzberg during the course of 1923 to meet with Eckart at Pension Moritz and plan the future course of the Nazi party. These meetings with Eckart gave rise to many of the party’s early plans, including that to seize power in Bavaria by marching on Munich in November 1923.

The attempted coup (known as the Munich Putsch) ended in gunfire, where state police were able to stop the 2,000 party loyalists at the Feldhernnhalle in central Munich. Hitler was arrested two days after the failed Putsch, along with Eckart who was finally taken into custody from his mountain hideaway.

Put on trial three months later for high treason, Hitler was convicted and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. He nevertheless received preferential treatment in Lansberg prison owing to the political volatility of the time; he was able to receive guests, dress smartly and even have access to his loyal party deputy Rudolf Hess.

Eckart, suffering from heart problems, was released from custody shortly before Christmas 1923, but died a few days later in Berchtesgaden.

It was his period of time in Lansberg prison that enabled Hitler to reflect on his political strategy and work on the first volume of his political manifesto, entitled ‘My Struggle’, (Mein Kampf in German). This work was no doubt shaped to some degree by his mentor Eckart and their time together on the Obersalzberg.

Just months into his sentence Hitler was off the hook, partly due to intense lobbying and partly due to the increasing support for the party he represented. The supreme court of Bavaria issued a pardon and he was released on the 20 December 1924. It wasn’t long before he was back in Obersalzberg, this time persuading the managers of Pension Moritz to lease him a small wooden hut close to the guesthouse. Here he could complete work on his political manifesto, with no interruptions.

3. The transformation begins: The old Obersalzberg gives way to the new chancellor

Returning to Obersalzberg after his time in Lansberg prison, it would take Hitler just eight years to become Chancellor of Germany and acquire his own property on the mountainside.

After his early release from Lansberg, Hitler was forbidden from speaking in public for a period of two years. With the first volume of his political manifesto “My Struggle” (Mein Kampf in German), published in 1925, he used the seclusion of a rented hut close to Pension Moritz on the Obersalzberg to work on the second half of the text.

Whilst writing on the Obersalzberg, Hitler also turned his attention inwards upon the Nazi party itself. He managed to overcome the various differences in opinion and infighting within the party to assume overall control as the party’s self-styled leader, or ‘Führer’ in German.

By spring 1927 the ban on public speaking had elapsed and Hitler was able to openly address crowds again, speaking as leader of the Nazi party and generating renewed interest in his political manifesto.

Slowly, the royalties from sales of Mein Kampf began to add up and, combined with a continued desire to spend as much time as possible at Obersalzberg, Hitler looked for somewhere more substantial to rent. Opportunity knocked in 1928, when the chance to rent Haus Wachenfeld, a typical half-timber Bavarian chalet, from the widow of a north-German businessman arose. Hitler paid 100 Reichsmarks for the property per month, employed his half-sister Angela Raubel to manage the household and funded many renovations personally.

Meanwhile, back in the world of politics, the Nazi party was making limited progress. Up until the late 1929 the party had only ever received around 2-6% of the votes in the free elections of the late 1920s. Then came the Wall Street Crash of October 1929.

The crash and economic depression that followed changed the prospects of the party dramatically. Many German banks collapsed and wide-spread unemployment took hold across Germany.

The Nazi party saw their chance and campaigned on the promise to strengthen the economy and create jobs. Unemployment increased to a peak of around 30% in 1932, further improving the prospects of the party and growing their share of the public vote to 37%.

By late 1932, after two inconclusive elections in June and November and the absence of an effective government, it was clear that the Reich President von Hindenburg needed to form a capable new cabinet as soon as possible. With the assurance from Vice-Chancellor von Papen that the Nazi Party could be controlled, three posts in the new cabinet were given to members of the Nazi party in recognition of their strong polling results.

Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor on the 30th January 1933. In June of that same year he would purchase Haus Wachenfeld for 40,000 Goldmarks and return to Obersalzberg as Chancellor of Germany.

4. Takeover of Obersalzberg: A second seat of power for the Nazi party emerges

Returning to Obersalzberg as Chancellor of Germany and owner of Haus Wachenfeld in early 1933, it wasn’t long before other party members followed Hitler to Obersalzberg to the detriment of the original community. The first to accompany him was fellow cabinet member, and later Reichsmarschall, Hermann Göring. Göring had also personally bought land on the Obersalzberg and began work on his own country house, complete with swimming pool.

As the Obersalzberg became a more important location for the party one of its members was tasked with converting the area into an effective second seat of power – Martin Bormann.

Bormann had been the manager of an agricultural estate in Weimar Germany before joining the party in 1927 and, playing to his strengths in organisation and finance, took on similar roles within the party.

His successful management of the party’s accident insurance fund saw him rise swiftly through its ranks, becoming the personal secretary to the deputy leader Rudolf Hess in 1933, Reichsleiter (national leader – the highest party rank) in late 1933 and by 1934 a member of Hitler’s inner circle.

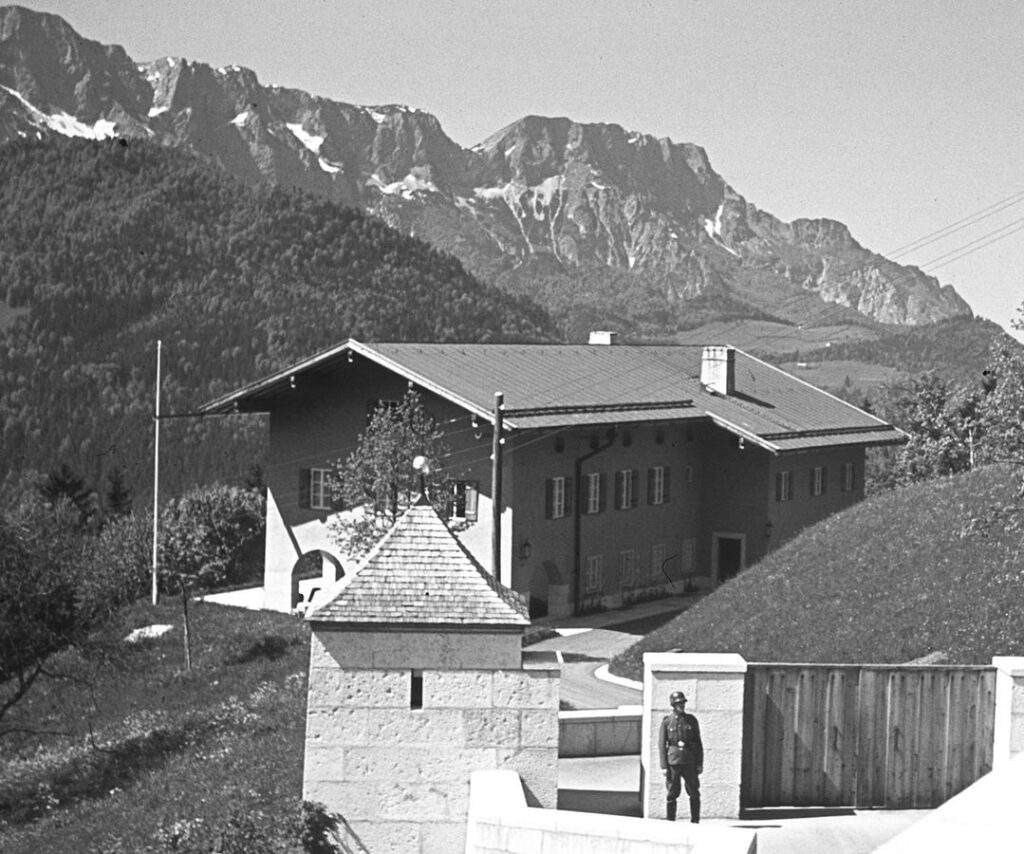

Just a year later, Bormann was tasked by Hitler to oversee the securing and re-development of the Obersalzberg. This started with the conversion of the once modest Haus Wachenfeld into the sprawling Berghof, where Hitler would spend around a third of his time from 1923 to 1945.

Bormann also focused on increasing the security of the area and was keen to force out the owner of neighbouring Hotel Zum Türken, owing to the fact that it overlooked the Berghof. The owner of the hotel, Karl Schuster, was understandably opposed to any sale, however, after his business way boycotted and a three week stay at Dachau, he came around to Bormann’s offer – despite it being significantly below market value.

Thus, Bormann was able to convert the Hotel Zum Türken into the headquarters for the security forces (Reichssicherheitsdienst) and set up the inner off-limits area around the Berghof and surrounding property. He next turned his attention to the wider Obersalzberg and his desire to create a second, much wider off-limits area.

After a handful of market transactions with local landowners as per the Hotel Zum Türken takeover, Bormann resorted to force to ensure that, between 1935 and 1937, he was able to acquire the vast majority of the 50 homes and businesses (800 hectares of land) that made up the old Obersalzberg. These transactions were often conducted under duress and it wasn’t uncommon for vendors to find their roof gone to expedite their vacating the property.

The expulsions were indiscriminate. Along with those who had called the Obersalzberg home for generations, the great and good who had also moved to the area in more recent times, such as Bechstein and the owners of the Platterhof Hotel, were also forced to leave. So, with Hitler’s personal fortune amassed from increasing sales of Mein Kampf and significant Party funds, Bormann was able to secure the wider area surrounding the Berghof and provide a blank canvas for construction of the National Socialists’ second seat of power.

5. Transformation of the Obersalzberg

Once Bormann had secured the majority of land on the Obersalzberg he demolished practically all of the original buildings and set about building a small town on the mountainside.

Bormann had access to between 3,000 and 6,000 workers to enact the grand plans for the Obersalzberg. From early 1937 these workers were Germans, Austrians and Italians and paid well thanks to the involvement of large German building companies like Frankfurt-based Polensky & Zöllner. As 1938 approached and Germany prepared for war, more and more of the gaps in the workforce were filled by Czechs and Poles. These replacement workers had to endure lowering wages and increasingly testing working conditions; harsh alpine weather, meagre rations and long periods away from home were commonplace.

By the end of 1938 most of the construction work had been completed, with Bormann personally overseeing the completion of homes for many of Hitler’s inner circle. The following support buildings were also commissioned, illustrating how the Obersalzberg really had become a small town:

- Greenhouse, some 110m (360ft) long to support Hitler’s vegetarian diet with fresh vegetables year-round

- Mooslahnerkopf tea house, built for personal visits across the meadow from Hitler’s Berghof

- Coal bunker, as the majority of the Obersalzberg’s furnaces were powered by coal

- Hotel Zum Türken, latterly a security forces HQ on the Obersalzberg

- Buchenhöhe settlement, some 40 apartment blocks for officials and their families

- Klaushöhe settlement, 32 large houses for married SS officers and their families

- SS Barracks, housing some 300 SS soldiers and their training facilities

- Kindergarten, to cater for the young children of the SS men and administrative staff of the Obersalzberg

- Hotel Platterhof, now reconfigured as a 150-room hotel for party members’ exclusive use

- Platterhof personnel building, a three-level administrative structure housing the Platterhof staff

- Guesthouse Hoher Göll, previously part of the Platterhof this now served as a party guesthouse for VIPs

- Gutshof, a model farm created by Bormann (a former farmer himself) to serve as a blueprint for farms to be built in conquered territories

- Movie theatre/cinema, owing its existence to Hitler’s love of film and seating some 2,000 in total

- Model gallery, to showcase the structures to be built both in German and conquered territories

- Motor pool, housing the vehicles used by the Obersalzberg administration and their drivers

- Worker’s camps, to house up to 6,000 workers involved in the construction work on the Obersalzberg.

- 6km (4miles) of underground bunkers, built mainly in the latter half of the second world war to shelter the inhabitants of the Obersalzberg as air raids became a very real threat

Even with such a vast quantity of structures in the pipeline, Bormann still wanted to undertake another project that would act as the crowing feature of the new second seat of power for the National Socialists on the Obersalzberg.

Bormann took inspiration from Hitler’s affinity for the Mooslahnerkopf teahouse opposite the Berghof and the way that Hitler used the Berghof in Obersalzberg to receive foreign diplomats and heads of state rather than Berlin. He planned a larger Teahouse that could also act as a diplomatic stage. And what more audacious stage for international relations than atop the Kehlstein mountain, towering over the Obersalzberg at a height of 1,881 metres (6,171 ft).

6. Construction of the Eagle’s Nest and Eagle’s Nest Road

It was April 1937 when Bormann began the project to build a structure on top of the Kehlstein mountain above the Obersalzberg. As with most buildings atop mountains in Germany, the German name for the Eagle’s Nest – and that used by the National Socialist administration – was the Kehlsteinhaus: literally, the Haus on the Kehlstein mountain.

Bormann had expert support from Dr Fritz Todt, chief engineer of road construction in Germany at the time and later armaments minister and architect Professor Roderick Frick. Todt’s input shaped the layout of Eagle’s Nest road dramatically, since he persuaded the usually unpersuadable Bormann to amend his planned route up the mountain.

Bormann’s original plan was to construct a road that wound up the mountain fairly directly and terminated at the peak, where up until then only a few footpaths and hunting huts (favourites of Herman Göring) had resided. Todt persuaded him that the road should work with the mountain rather than against it and make use of the natural rock formations, terminating below the peak and find an alternative means of ascending the last few meters. This plan ensured that the outline of the mountain wouldn’t be spoiled by vehicles.

With Todt’s input, work began in June 1937. Some 3,000 paid workers from Germany, Austria, Italy, Czechoslovakia and Poland were housed in five barracks all over the mountain and put to work immediately. Their first undertaking was the access network necessary to facilitate construction work. Some 17 kilometres (11 miles) of access roads were cut into the mountain to enable transport of men and materiel, many of which were fitted with rails to further increase productivity.

By October 1937 a cable car had also been constructed to enable transport of material directly from the Obersalzberg to the building site atop the Kehlstein mountain.

Winter in the mountains was particularly harsh but this did not deter Bormann, who, despite obvious costs to efficiency, ordered that work should be undertaken throughout the winter of 1937-1938.

Not only was work to continue throughout all weathers, but it was to also continue around the clock, courtesy of searchlights, gas lamps and increases to wages. He wanted to complete the project in time for Hitler’s 50th Birthday in April 1939.

This superhuman effort, coupled with exquisite engineering, yielded no less than 17km (11 miles) of roads across the mountain, of which the main route up to just below the peak of the Kehlstein mountain accounted for 6.5km (4 miles). This main route up to the planned structure atop the mountain made its way through five separate tunnels, ascended 800 meters from the Obersalzberg and was even equipped with telephone pillars every few hundred meters to ensure communications were open at all times.

By August 1938 road tarring had begun, whilst Borman, Todt and Frick had come to a solution to ascend the final 124m (406ft) from the terminus of the road to the peak of the mountain: a lift (elevator). Where the newly constructed main road ended a tunnel was blasted into the mountain and, where it finished, a shaft bored out of the rock to lead directly up into the Eagle’s Nest itself. Both the entrance tunnel and lift shaft measured 124m (406ft) exactly.

Against the backdrop of good progress on the road network, Professor Frick’s attention turned to starting construction of the structure at the peak of the mountain. With the cable-car operational and the worst of the winter behind him, he commenced work at the Kehlstein peak in February 1938.

The site swarmed with workers, often numbering close to 1,000 and under pressure to complete their work as swiftly as possible. Cramped working conditions and scaffolding boards perched atop precipices were a daily hazard as they toiled to erect the timber form of Professor Frick’s design for the structure atop the Kehlstein mountain.

Once Bormann was happy with the timber form, it could serve its main purpose as a concrete form. From the outset the structure was engineered to have a re-enforced concrete core for strength and speed of erection. Once the concrete had set, swarms of masons clad the interior and exterior with blocks of limestone and granite respectively.

This created the aesthetic of a castle perched atop a mountain that Professor Frick wanted to capture. Each stone was cut to a specific design and thus had to be numbered and installed accordingly by the firm Phillip Holzman from Passau; nothing was out of the question for the masterpiece of Bormann’s re-imagined Obersalzberg.

Power for the installation was provided by an underground cable that ran along the Kehlriedl ridge from the Obersalzberg up to the Kehlstein mountain. In case of emergency, a backup generator was installed in a cavern at the foot of the lift shaft.

A MAN U-Boat diesel engine was chosen to provide the necessary backup power in case of a supply failure from the Obersalzberg. This U-Boat engine is still in situ and fully operational condition to this day.

By October 1938, after just 16 months, the project was complete. 3,500 men had taken part in the building of the road network and structure atop the Kehlstein mountain and, thanks to their superhuman efforts and party funds equivalent to around €150 million in today’s money, they had accomplished the most audacious construction project of the Obersalzberg in double quick time. Finally, Bormann had his crowning feature of the re-built Obersalzberg. The Eagle’s Nest (officially, the ‘Kehlsteinhaus’) was complete.

7. Use of the Eagle’s Nest from 1938 to 1945

The Eagle’s Nest is best thought of as a symbol of the National Socialists Regime’s power. Power on a practical level, evident in the first-class engineering solutions and craftsmanship on show, and also power of a more conceptual variety.

Here we have an almost medieval castle-like structure high on the Kehlstein mountain echoing Hitler’s dictatorial position in the world and fondness for emulating historical leaders like Charlemagne, whose kingdom Hitler sought to replicate with his own third kingdom (third Reich). Here atop the Kehlstein mountain Hitler could look down to both Austria and Germany as he sought to build his new third empire after the bitter disappointment of 1918 and the fall of Bismark’s second kingdom (second Reich).

This power was communicated by using the Eagle’s Nest as an entertaining destination for visiting dignitaries, a diplomatic house of sorts. Indeed, it was the French ambassador, André François-Poncet, who was one of Hitler’s first visitors to the newly completed Eagle’s Nest in 1938. No doubt this was the perfect stage for Hitler to intimidate the French ambassador, however what wasn’t expected was the origination of the term we use (in English) to refer to the building today: Eagle’s Nest. It was François-Poncet who coined the term “Eagle’s Nest” in his write-up of the visit in the French press and it resonated with non-German speakers, who found Kehlsteinhaus rather abstract.

Hitler made just 14 official visits to the Eagles Nest between September 16th 1938 and October 17th 1940, typically in the company of his generals and diplomats from foreign powers. From October 1940 onwards, no further visits were made, perhaps indicating that the time for diplomacy was well and truly over.

The Eagle’s Nest was only occasionally used between 1940 and 1945, typically by Martin Bormann or Eva Braun.

A large number of photos and videos from Eva Braun’s personal collection feature the Eagle’s Nest, such as her sister’s wedding celebration on June 3rd 1944, just three days before the Normandy landings. The party was arranged by Eva for her sister Gretl Braun, who was to marry Herman Fegelein, a member of Heinrich Himmler’s staff.

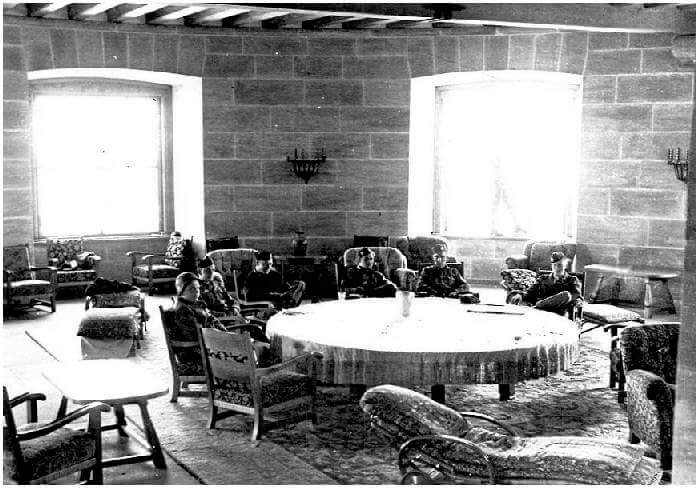

Eva Braun’s cinefilms caught much of the wedding and subsequent celebration on the Obersalzberg and at the Eagle’s Nest on film, showing us that in the Great Hall of the Eagle’s Nest the main tables and chairs were swapped for dining tables and, once the banquet was complete, cleared for an evening dance.

8. The allied air raid of April 1945 and survival of the Eagle’s nest

The mission sheet prepared for the allied air raid on the Eagle’s Nest and Obersalzberg complex was dated 5th October 1944 and gave clear instructions that both the Eagle’s Nest and Obersalzberg were to be targeted.

The raid itself took place on the morning of 25th April 1945 and was well-prepared; some 400 Lancaster and Mosquito bombers of the British RAF closed in on the area at an altitude of just 400m and, using the mountains as cover right up until the last minute, spent 90 minutes dropping some 1200 tonnes of munitions on the targets amid sporadic flak from what little anti-air manpower was left in the Berchtesgaden area.

Given that the war was all but finished in Europe, it could be considered that this raid on the Obersalzberg in April 1945, the last major air raid of World War 2, was a political act more than military necessity.

The raid saw the 3,500 inhabitants of the Obersalzberg (including Hermann Göring) take to the network of underground tunnels for shelter. Despite the liberal use of 12-tonne Tall Boy bunker-busters by the RAF, only 30 deaths were recorded in the raid. Above the tunnels was a very different story; nearly every building in the main Obersalzberg off limits area had sustained either direct hit(s) or collateral damage.

Every building, that is, except for the Eagle’s Nest. Whether or not this was deliberate is a point open for discussion.

On the one hand, it was a very small target on the top of a ridge and thus very difficult to aim for, something that was exacerbated by the snow on the roof and surrounding ground that cold April morning.

On the other hand, perhaps the Eagle’s Nest was saved as a trophy? This line of thought would certainly fit with the behaviour of the American armed forces immediately after the war, who effectively seized the Obersalzberg in 1945, declared it entirely off limits until 1949 and only finally left the area in 1995.

The days and weeks after the air raid of 25th April were marked by exploration and plundering of the Obersalzberg by the local population. The Eagle’s Nest was safe, thanks to the snowfall effectively sealing off the road and path network to the peak of the Kehlstein mountain.

On May 4th, the allied troops entered Berchtesgaden, keen to be the first to liberate the Obersalzberg.

It’s a moot point as to who got there first, but consensus is that there are two main contenders: the American 3rd Infantry and the French 2nd Armoured Division. Hot on their heels was the American 101st Airborne division, who were met by local District president Theodor Jakob, keen to peacefully surrender the entire Berchtesgaden area.

On the next day, 5th May, these Allied units held a flag-raising ceremony on the hill in between the smouldering ruins of Göring and Bormann’s homes to mark the liberation of the Obersalzberg and, effectively, the defeat of the final major headquarters of the National Socialist regime.

Some 3 days later, victory in Europe was declared. To control looting and keep order amongst the occupying US and French troops, a military government was quickly set up by the Americans who appointed local governor Dr Theodor Jakob as County Commissioner.

9. Use of the Eagle’s Nest after 1945

Immediately after the war, the Eagle’s Nest and ruins of the Obersalzberg were declared off limits – not for the first time in their history. This time, the area was the preserve of the Allies’ military leaders and their troops, who effectively came on sightseeing trips.

Visitors including Dwight D Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery were able to tour the remains of the Berghof, explore the underground tunnels commissioned by Bormann and take a jeep ride up the winding road all the way to the top of the Kehlstein mountain. There they could, if they were officers or higher, ride in the brass elevator and enjoy a private walk through the Eagle’s Nest and Kehlstein peak. Some VIPs were even driven up the Eagle’s Nest road in Hitler’s armoured Mercedes, recovered from the Obersalzberg.

This arrangement came to an end when, in 1949, when the US armed forces finally opened the Obersalzberg to the German public – for the first time since 1933. It wasn’t a complete return, since the US Armed forces choose to retain some 40 buildings on the Obersalzberg and in the wider Berchtesgaden area as a new rest and recuperation facility.

This arrangement came to an end when, in 1949, when the US armed forces finally opened the Obersalzberg to the German public – for the first time since 1933. It wasn’t a complete return, since the US Armed forces choose to retain some 40 buildings on the Obersalzberg and in the wider Berchtesgaden area as a new rest and recuperation facility.

The Hotel Platterhof, where the relationship between the National Socialists and Obersalzberg began, was refurbished and re-opened as the US Armed forces’ Hotel General Walker. Martin Bormann’s model farm and meadows were even converted into a golf course and ski centre.

Continued tourism interest led the Bavarian State Government to order the destruction of the ruins on the Obersalzberg not occupied by the US Armed Forces in 1952. The clearance was intended to deter misguided interest and remove potential pilgrimage sites, including the remains of Hitler’s Berghof. One exception was successfully argued by commissioner Theodor Jakob: The Eagle’s Nest.

His argument was that a tourist bus service and facility that used the Eagle’s Nest could be established to support a newly set up ‘Landesstiftung’ – a non-profit community body – to support local projects with the profits from the site.

The argument was further strengthened by the fact that the road to the summit of the Kehlstein mountain had been handed back to the German administration in 1951 and was in good repair.Thus began the bus service that you can enjoy today, some 68 years after its inception.

It’s that same community body that is supported by your visit to the Eagle’s Nest and its restaurant today, although it’s worth noting that from 1952-1962 the Eagle’s Nest was actually run by the German Alpine Association primarily as a base for mountaineers and hikers, rather than as a busy mountain-top restaurant.

10. A new millennium: The Documentation Centre and a five star hotel

In 1995 the US armed forces finally vacated the Obersalzberg and returned all property that they had used as the rest and recuperation centre back to the state of Bavaria, including the former Platterhof Hotel and the Gutshof model farm.

This left the authorities with something of a dilemma, since they knew from the visitor numbers at the Eagle’s Nest that the Obersalzberg played an important part in the local economy, however, they were also keen to ensure that the Obersalzberg and the remains of the National Socialist complex there did not become a source of unwanted attention.

Thus, they embarked upon a plan that would both record the Obersalzberg’s historical significance and re-establish the location as a mountainside holiday destination by undertaking two construction projects.

Where the foundations of the former National Socialist Party Guesthouse “Hoher Göll” stood, you’ll now find the Documentation Centre Obersalzberg.

This is an outpost of the Institute for Contemporary History in Germany and is designed to explain through three levels of well curated exhibitions the history of the Obersalzberg, the National Socialist rise to power, the key figures in the regime, the regime’s methods of control, antisemitism, concentration camps, a wider overview of the Second World War and the presence of the US armed forces in Berchtesgaden up until 1995.

The documentation centre also yields access to part of the tunnel system that belonged to the guesthouse Hoher Göll and the Platterhof. Entry to the tunnels is included in admission to the centre and provides first hand insight into the scale and sophistication of the underground labyrinth that Bormann commissioned as air raids in south Germany became a real threat.

When the Documentation centre first opened it was primarily intended to cater for German visitors who were attending as part of their history studies. As such the centre was designed to accommodate 30,000 visitors a year and all exhibits were produced in German only.

The reality is that up to 170,000 visitors attend the centre each year, a large proportion of whom don’t speak German. Leaflets and audio guides have been developed to cater for the most popular non-German languages but as it stands, the centre us currently undergoing a €30 million extension that will cater for the wider audience from early 2021.

The second key project to re-establish the Obersalzberg as a destination was the creation of an ambitious new five-star alpine hotel on the hill where the homes of Hermann Göring and Martin Bormann once stood, a site that the Eagle’s Nest busses also departed from.

The General Walker hotel (formerly the Platterhof hotel) was torn down in 2000 to make way for a new car park and the Eagle’s Nest bus departure point moved to the former site of the hotel Platterhof’s garages. Just a few years later, in 2005, the five-star Intercontinental Hotel Berchtesgaden could finally open. Offering 138 luxurious rooms, Michelin-starred dining and heated mountainside swimming pools, traditional high-class tourism had finally returned to the Obersalzberg.